Slow, Not Steady: Assessing the Status of India-Eurasia Connectivity Projects

Author: AYJAZ WANI

India’s robust economy has tremendous potential. But for sustained economic growth, it needs direct access to the Eurasian markets, backed by reliable, resilient, and diversified supply chains. Indeed, enhanced connectivity with Central Asia and the wider Eurasia is essential to promote regional stability and unlock economic opportunities for all countries in the region. This paper analyses the status of the key connectivity projects in the region, and the challenges and opportunities for India.

Introduction

In the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union and the subsequent emergence of independent republics in Central Asia, India redesigned its ties with the region through diplomatic initiatives and visits, financial aid, and capacity building (training programmes, study tours, and technology transfers under the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation programme). In 2021, India launched the ‘Connect Central Asia’ policy to enhance the political, economic, cultural, and historical relations with the region.[1] However, connectivity between the two regions is in bad shape. This is often cited as the most prominent hindrance to regional development and the cause of the trade deficit between India and Central Asia. Given its critical role in regional development and social prosperity, there is a need to achieve maximum connectivity for socioeconomic development. Consequently, agreements between India and Central Asian countries at the bilateral and trilateral levels and legal and administrative frameworks have aimed at easing procedures for the movement of people and goods across the region and beyond.

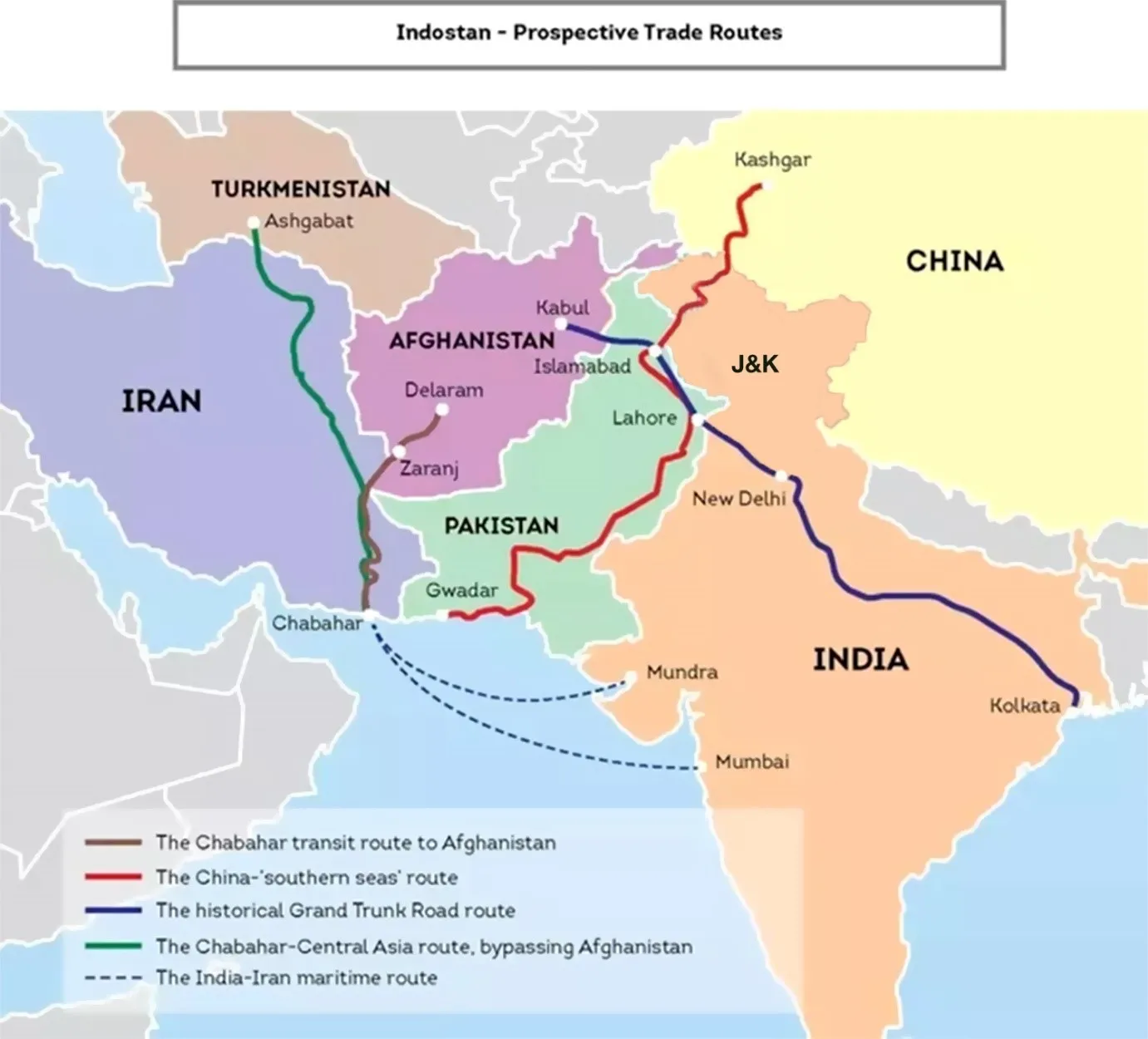

However, although many connectivity projects have been in the pipeline for decades, little progress has been made, primarily due to geopolitical factors. The non-viability of access routes through Pakistan and Afghanistan continues to be an obstacle and will likely remain so for the foreseeable future. Pakistan has blocked the strategic, economic, and cultural interests of both regions by refusing to facilitate connectivity via its territory. For instance, the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline, which has the potential to meet South Asia’s energy needs, has been stalled since 2006 due to heightened security concerns.[2]

Perhaps under China’s influence, Pakistan has continued to create roadblocks for India in establishing strong trade and economic relations with the Central Asian/Eurasian countries. Hostility between India and Pakistan benefits China’s hegemonic pursuits in Eurasia through its much-hyped Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Indeed, Beijing has sought to expand its commercial footprints in Central Asia, strategically located at the crossroads of Asia and Europe. While inaugurating the BRI in Kazakhstan in 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping said that all Central Asian countries should take an innovative approach and collaborate with China in setting up “an economic belt along the Silk Road”.[3] Additionally, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship BRI programme with US$62 billion-worth of investments in energy and infrastructure projects in Pakistan, has added to India’s geostrategic, geoeconomic, and security concerns. CPEC spans through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and violates India’s sovereignty, resulting in strong opposition from New Delhi.[4]

As a result, India has explored other options to establish connectivity with the hydrocarbons-rich and geostrategic Central Asia. It has invested in the Chabahar Port in the Iranian province of Sistan-Balochistan and signed an intergovernmental agreement for the 7,200-km International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) between Iran, Russia, and India. Such proactive and well-meaning pursuits for connectivity paved the way for India’s admission to the Ashgabat Agreement in 2018. Subsequently, the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018 and the imposition of stricter sanctions on Iran created problems for India’s infrastructure projects in the form of an investment crunch, bureaucratic delays, and inter-regional disputes. Despite these numerous setbacks, the Chabahar Port and the INSTC are progressing, albeit slowly; in July 2022, the first shipment through the INSTC arrived at Mumbai’s Jawaharlal Nehru Port from Russia’s Astrakhan Port.[5]

However, despite the historical ties, the positive perceptions about India in Central Asian Republics (CARs), and the immense potential for trade owing to Central Asia’s rich energy resources and India’s largely import-dependent energy requirements, trade ties between India and Central Asia and greater Eurasia remain nominal. Recent developments in Afghanistan have made the Central Asian region even more crucial to India’s interests but have also dampened the prospect of using the Chabahar Port route through that country to access the CARs.

This brief attempts to trace the history of three key India-Eurasia connectivity projects—Chabahar Port, the INSTC, and the Ashgabat Agreement for multimodal connectivity—and take stock of their status.

Chabahar Port

In 2003, India announced plans for investment in the Chabahar Port in Iran’s Sistan-Balochistan province to gain access to Central Asia,[6] signing a memorandum of understanding with Iran in 2015. The project gained traction in 2016 when Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India would invest US$500 million in developing the Chabahar Port.[7] In 2018, India Ports Global Limited operationalised the port’s Shahid Beheshti terminal with equipment worth US$25 million, including six mobile harbour cranes—two with 140-tonne capacities and four with 100-tonne capacities.[8] Between 2019 and 2021, 123 vessels and 1.8 million tonnes of bulk and general cargo passed through Chabahar.[9] By August 2022, the terminal had handled over 4.8 million tonnes of bulk cargo, including transhipments from Bangladesh, Brazil, Australia, Germany, UAE, and Russia.[10] India also shipped 75,000 tonnes of wheat to Kabul in 2020 as part of a humanitarian aid programme via this strategic port.

Map 1: India’s proposed connectivity projects and China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

India also boosted connectivity with war-torn Afghanistan via the Chabahar Port. It invested an estimated US$3 billion in civic infrastructure, including the 218 km-long Zalranj-Delaram Highway that connects Afghanistan to the Chabahar Port via Milak in Iran. The Zalrang-Delaram strategic highway connects 2,000 km of the Afghanistan Ring Road, linking 16 provinces (including Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif, Kabul, Ghazni, and Kandahar) to Tajikistan.[12]

In 2018, the Donald Trump administration in the US unilaterally withdrew from JCPOA and targeted Iran’s economy with over 960 sanctions,[13] which drove Iran into recession and affected India’s desire to convert its commitments into concrete actions. Subsequently, during the US-India 2+2 dialogue held in 2019, New Delhi secured narrow exemptions for developing the Chabahar Port,[14] including on the facilitation of funds from global banks to purchase equipment worth US$85 million for warehouses, cranes for loading and unloading, and multipurpose terminals at the port. The exemptions also included constructing a railway line from Chabahar Port to the Afghan border.[15] These exemptions were granted based on certain assurances made by India, primarily that Iran’s Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) would not participate in the project.[16] However, the fear of secondary sanctions has made procuring equipment from private infrastructure companies challenging. Despite these uncertainties, India doubled budgetary allocations for port development from US$5.5 million in 2020-21 to US$12.3 million in 2022-23.[17]

In 2016, India and Iran signed an agreement to construct the 628 km-long Chabahar-Zahedan railway line. Although state firm Indian Railway Construction Limited completed the site inspection and feasibility report, the two sides diverged on some issues, particularly when New Delhi objected to certain entities that Tehran wanted to be a part of the construction project.[18] Tehran was keen to have Khatam al-Anbiya Construction Headquarter, a firm controlled by the IRGC, as part of the project. But since the US has proscribed the IRGC, India cannot work with the organisation or any of its subsidiaries despite gaining sanctions exemptions for the Iran connectivity projects.[19] Repeated funding delays by India led Iran to drop it from the railway project.[20] Iran has proceeded with the track-laying process, and the project is estimated to be completed by 2024.[21] Still, with work pending on less than 200 km of the track, Iran is now keen for India to complete the rest by partnering with a firm not connected to the IRGC.[22]

At the same time, landlocked Uzbekistan is keen to connect with India and West Asia via Afghanistan. In 2018, the Uzbek president floated a 650 km railway line between the Afghan cities of Herat and Mazar-i-Sharif, 80 km away from the Uzbek-Afghan border. Tashkent has already invested US$500 million in the project and has repeatedly sought to collaborate with New Delhi.[23] This project is expected to connect with the Chabahar-Zahedan rail track along the Iran-Afghanistan border.

Given the criticality of these connectivity projects to Central Asia, a trilateral working group was established in 2020 to seek convergence on Chabahar Port and other connectivity projects between Iran, India, and Uzbekistan. At its second meeting in December 2021, the group emphasised the importance of the Shahid Beheshti Terminal at Chabahar, and discussed further developing a transportation corridor between South Asia and Central Asia.[24]

Map 2: Chabahar-Zahedan railway line

International North-South Transport Corridor

The 7,200-km INSTC was first conceived under a September 2000 agreement between Iran, Russia, and India.[26] Since then, the INSTC agreement has been ratified by 13 countries, including Russia, India, Iran, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bulgaria, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Oman, Tajikistan, and Ukraine. However, the INSTC corridor remained stalled due to the United Nations sanctions on Iran. In July 2015, Iran and several world powers, including the US, concluded a nuclear agreement (the JCPOA). After the sanctions were eased, the INSTC gained momentum, and by 2018, around 11 million tonnes of goods were transported through the corridor.

The INSTC includes sea routes and rail and road links to connect Mumbai (India) to Saint Petersburg (Russia) via Chabahar. The INSTC is expected to decrease transit time by 40 percent (from 45-60 days to 25-30 days) and freight cost by 30 percent compared to the Suez Canal route.[27] Dry runs conducted between 2014 and 2017 showed a saving of US$2,500 per 15 tonnes of cargo.[28] For instance, the typical maritime route from Mumbai to Moscow is 8,700 nautical miles (16,112 kilometres) with a completion time of 32-37 days. The INSTC will curtail it to 2,200 nautical miles (4,074 kilometres) plus 3,000 kilometres (overland), requiring only 19 days. The 9,389 km-long New Delhi-Helsinki rail route proposed under the INSTC will take 21 days, compared to the conventional 16,129 km-long sea route, which requires 45 days.[29]

Map 3: International North-South Transport Corridor and other transport corridors

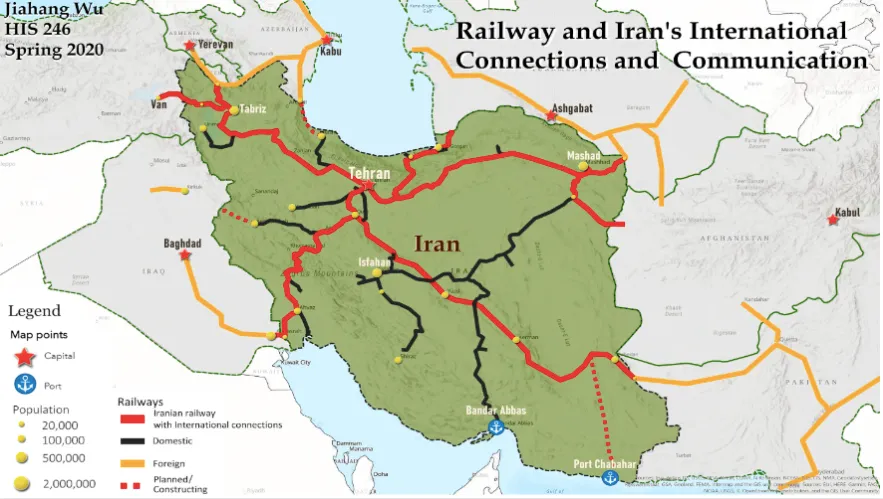

In 2016, Azerbaijan signed an agreement with Russia and Iran to establish a transport corridor between the three countries.[31] In 2017, the three countries agreed to reduce tariffs to encourage transborder trade via the INSTC. The same year, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) approved a US$400 million loan to modernise railway infrastructure within Azerbaijan, US$250 million of which was used to restore the 166-km double line main track on the INSTC between Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran.[32] In 2022, Azerbaijan received US$9.3 million in technical assistance to help develop sustainable transportation, especially railways.[33]

Baku also invested US$10 million to construct a 1,524 mm gauge 10 km railway line between Astara (Azerbaijan) and Astara (Iran), inaugurated in 2018. Both countries also entered into a 25-year agreement with Iran Railways for a 35-hectare freight transhipment facility run by Azerbaijan’s national railroad operator.[34] In March 2019, the 175-km Qazvin-Rasht railway line between Azerbaijan and Iran was inaugurated.

In 2020, cargo transit between Iran and Azerbaijan increased to 480,000 tonnes despite the COVID-19 pandemic, with US$339 million in bilateral trade.[35] In January 2021, the two countries signed an agreement on railroad cooperation to boost cargo volume to two million tonnes annually.[36]

Map 4: Iranian Railway and International connections

The Qazvin-Rasht railway line was designed to link to the Rasht-Astara railway (see Map 4), a central part of the INSTC. However, Tehran’s technical and financial challenges have led to considerable construction delays. Iran and Russia are currently in talks to expedite the construction of this vital 164-km railway line to connect the cities of Rasht and Astara via Anzali.[38] In 2016, Azerbaijan agreed to finance the project with Iran jointly,[39] but the agreement was not implemented because of the US sanctions. Desperate to complete the Rasht-Astara railway link, Iran and Russia finalised their previously-agreed US$5 billion credit line to complete several development projects in Iran,[40] including the railway line.[41] The construction, expected to complete in 2025, will cost an estimated US$2 billion.[42]

Ashgabat Agreement for Multimodal Connectivity

In April 2016, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Oman, and Qatar signed the Ashgabat Agreement to facilitate trade, transport, and transit connectivity within Eurasia and synchronise it with other regional transport corridors such as the INSTC between Central Asia and the Persian Gulf. Subsequently, Pakistan and Kazakhstan joined the agreement in 2016 and India in 2018. The Ashgabat Agreement allowed New Delhi to access the Central Asian markets and the region’s high-value mineral reserves, including uranium, copper, titanium, ferroalloys, yellow phosphorous, iron ore, and rolled metal, by bypassing Pakistan’s hostility and Afghan instability.[43]

The 928-km Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran (KTI) railway line running east of the Caspian Sea, which became operational in 2014, is a significant route under the Ashgabat Agreement.[44] Its construction began in 2009 following a trilateral agreement between the three countries in 2007. The Islamic Development Bank contributed US$370 million to KTI’s total cost of around US$1.4 billion. The route connects Uzen in Kazakhstan with Gyzylgaya, Bereket, and Etrek in Turkmenistan, and terminates at Gorgan in the Iranian province of Golestan.[45] This route gives landlocked Central Asia access to Iran’s seaports. In 2021, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan agreed to boost and expand the cargo volume via this route.[46] The KTI rail line connects with the Tsarist-era Trans-Caspian Railway in Bereket, which travels across Turkmenistan and further into Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. The KTI line runs on a 1520 mm gauge until Etrek, and then a standard gauge in Iran.[47]

The KTI line has been formally included in the INSTC and the Almaty-Bandar Abbas corridor, entering Iran through the border point of Sarakhs. With a capacity to carry two million tonnes of goods annually on the Almaty-Bandar Abbas corridor, the 3,756-km line connects Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan.[48]

During the first India-Central Asia summit, held virtually in January 2022, all countries stressed the inclusion of the Chabahar Port into the INSTC. They also noted Turkmenistan’s proposal to include the Turkmenbashi Port within the INSTC’s framework. Located on the Caspian Sea, the port handles ships moving freight from one train to another on both sides. A multimodal service that operated straight between Russia and Iran across the same landlocked “sea” was already operational. The INSTC will acquire more route options by adding Turkmenistan to the project. Given their preference to use the Chabahar Port to facilitate trade with India, the CARs have welcomed New Delhi’s proposal to establish a joint working group on services and the hurdle-free movement of goods between the two regions through the port.[49]

India’s Role in Connectivity Projects: Challenges and Opportunities

The CARs view Indian connectivity projects as a game changer for the region. Given its sustained economic transformation and growth, the CARs see India as a crucial player in the Eurasia region, and have increased their engagements with New Delhi through different multilateral and bilateral platforms on trade, connectivity, and security. Connectivity should be a key priority for India to secure its interests. At the same time, the CARs need enhanced regional and cross-regional connectivity for socioeconomic development and to diversify trade. As such, the India-led connectivity projects are seen as an opportunity, but there are some challenges that must be overcome.

Challenges

Most of the INSTC projects (except for the Azerbaijan and KTI railway lines), the Chabahar Port, and Ashgabat Agreement transport corridor have not received financing from the major global financial institutions such as the World Bank, ADB, European Investment Bank, or Islamic Development Bank. The primary cause for this was Washington’s unilateral sanctions regime against Tehran and fear of so-called ‘secondary sanctions’.

The imposition of harsher sanctions on Iran following the US’s withdrawal from JCPOA forced many global firms to exit connectivity projects in Iran. For instance, German business group Siemens halted its railway projects in Iran over sanctions fears in 2018;[50] Swiss company Stadler Rail abandoned its US$1.4 billion railroad deal;[51] a US$1.37-billion deal between the Iranian state rail corporation and its Italian counterpart to construct a high-speed rail line connecting the cities of Qom and Arak was halted; and South Korean business Hyundai Rotem cancelled its agreement with Iran’s state-owned railway corporation to manufacture 450 suburban railbus train cars.[52] Foreign direct investment into Iran decreased, from US$5,019 million in 2017, to US$2,373 million in 2019 and US$1,342 million in 2020.[53] According to the World Bank, Iran’s net capital growth rate worsened since 2014-15, impacting investments in machinery and equipment, and the downward trend in capital accumulation has only strengthened after the sanctions of 2018.[54]

The US’s assertive policy against Iran made China more proactive in the region. In 2020, a leaked draft agreement between Tehran and Beijing outlined the framework for increased Chinese investments in Iran and the latter’s integration with BRI. China invested US$26.92 billion in Iran between 2005 and 2019. Of the US$26.92 Chinese investments, US$1.53 billion were invested in chemical industries, US$11.1 billion in energy, US$4.96 billion in metals, US$160 million in real estate, US$6.92 billion in transportation, and US$2.25 billion in utilities.[55] Subsequently, using its bonhomie with Pakistan, China is also pursuing Afghanistan to embrace BRI, with plans to extend the controversial CPEC to the country.

The US sanctions also paved the way for Russia to make inroads in the region. Though marred by western sanctions, Russia has played a crucial role in the electrification and modernisation of the Iranian rail network. Russian Railways provided US$1.39 billion in financing for the electrification of the 495-km Garmsar-Incheboron rail line connecting with Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan.[56] However, the Russian-Ukraine war and the consequent economic sanctions on Moscow will adversely affect these connectivity projects, especially the Rasht-Astara railway link in Iran, slated for completion in 2025.

Despite gaining special waivers from the US sanctions, India slowed down the pace of investments in the Chabahar Port. It also restricted the 628 km railway line construction between Chabahar and Zahedan. India also stopped oil imports from Tehran. Although it spent US$12.3 million on the port construction in 2016-17, it failed to utilise the allocated US$18.5 million in the next year (2017-18). The 2018-19 budgetary allocation of US$18.5 million for Chabahar was also reduced to zero in the revised allocation.[57] However, in the years since, India has increased the budgetary allocations to Chabahar and other strategic connectivity projects. Iran is also willing to sign a long-term contract with India to complete the works at the Chabahar Port and realise its full potential in the coming years.[58] New Delhi has repeatedly pitched to include the Chabahar Port in the INSTC as “it is going to be one of the most important locations for global trade and maritime trade.”[59]

However, the pace of investments in Chabahar and other connectivity projects, including like 628-km Chabahar-Zahedan railway line, should be ramped up. For instance, India’s plan to invest US$1.6 billion in the railway line, which could have given the INSTC strategic heft against the BRI, is yet to materialise. Additionally, Iran and Russia’s concerns over foreign and private enterprises have contributed to these projects’ sluggish pace.

Opportunities

New Delhi has invested in the Chabahar Port to expand its influence into the Eurasian heartland by bypassing Pakistan. These investments support India’s more assertive and projective foreign policy attitude, especially after the pandemic and the Ukraine war created many obstacles in global supply chains.[60] During the 22nd meeting of the Council of Heads of State of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in September 2022, Modi urged the member countries “to make efforts to develop reliable, resilient and diversified supply chains in our region”.[61] Accordingly, he stressed better connectivity and full rights to transit within the SCO countries. At a meeting on the sidelines of the SCO summit, Modi and Iranian President Ebrahim Rais emphasised the value of bilateral collaboration in regional connectivity while reviewing the development of the Shahid-Beheshti terminal and Chabahar Port.[62]

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent supply chain disruptions highlighted the urgent need for an alternate logistics route. The crisis caused by a container ship that ran aground in the Suez Canal in March 2021, effectively halting cargo traffic between the Red and Mediterranean Seas, also highlighted the need to reduce the dependence on traditional routes.[63] The Suez Canal is a strategic route for natural resources, and “almost 10% of total seaborne oil trade and 8% of global LNG trade passes through” it.[64] Russia’s war in Ukraine also intensified the competition between Eurasian Economic Union and the European Union for economic integration with Eastern Europe. These events have amplified the need for the INSTC and other strategic connectivity routes as cheaper and faster alternative multimodal transit corridors aided by reliable, resilient, diversified supply chains. The Chabahar route and INSTC could boost trade from India to Eurasia by up to US$170 billion (US$60.6 billion in exports and US$107.4 billion in imports).[65]

The Chabahar Port and INSTC can harness the trade potential between India, Eurasian Economic Union, and Eurasia. The projects will fortify New Delhi’s geostrategic and geoeconomic engagement with the region and curtail Beijing’s hegemonic plans. Indeed, India received a waiver from the US sanctions on its connectivity projects within Iran[66] as it was perceived as a strategy to tame China’s growing hegemonic influence in Greater Eurasia. However, the waiver has not helped investor confidence in these India-led connectivity projects. The railway line between Chabahar-Zahedan is in dire need of investments. India must also seek to prioritise investments in the Zahedan-Mashad corridor, an ideal route to connect to Sarakhs (Turkmen border). The total distance from Chabahar to Sarakhs is 1,827 km, and this railway line can bridge the gap between INSTC, Chabahar, and Ashgabat Agreement.

Eurasia, South Asia, and Central Asia desperately need regional and cross-regional connectivity for socioeconomic development, trade, and intercultural exchange. With the inclusion of Pakistan and India in 2017, the SCO became one of the largest international organisations, accounting for about 30 percent of the world’s GDP and 40 percent of its people. India has become a loud advocate for regional and transregional connectivity, and must convince the SCO member countries, especially Russia and the CARs, to promote the Chabahar Port and INSTC projects.

India must prioritise investments in Eurasia and expedite free trade agreements (FTAs). The swift completion of the long-awaited FTA between India and the Eurasian Economic Union is in India’s best interest, given the region’s human and economic capital.

The connectivity projects can also help ensure greater regional harmony to tackle common challenges and geostrategic concerns, including Afghanistan. India must back the 650-km railway line project between the Afghan cities of Mazar-i-Sharif and Herat, which run through Shiberghan, Andkhoy, and Maimana in western Afghanistan. This trans-Afghan strategic railway line can link the CARs with Chabahar, with far-reaching implications for the region. Uzbekistan has already invested US$500 million in the project and has repeatedly sought New Delhi’s collaboration.

Lastly, as private investors are reluctant to invest in INSTC and Chabahar, New Delhi should provide tax breaks to Indian investors willing to explore Central Asian markets and invest in these strategic connectivity projects with some guarantees and sureties.

Conclusion

The India-led Eurasian connectivity projects have faced many economic and geostrategic challenges over the years that have slowed their progress. But these projects remain critical to the region, especially the CARs, to diversify their markets for imports and exports. These projects can also bring much-needed geostrategic cohesion and geoeconomic dynamism to the rest of the continent. India must expedite these projects, and policymakers must view investments in them as strategic, especially to counter China’s growing influence in the region. New Delhi must also jointly develop and strengthen cooperation in these projects with the CARs and Iran. Furthermore, India must leverage its ties with these countries through existing bilateral and multilateral agreements to prioritise the connectivity projects to promote regional stability and its role in the greater Eurasia.

Endnote

[1] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “Keynote Address by MOS Sri E. Ahamad at First India- Central Asia Dialogue”, Ministry of External Affairs, 2012.

[2] Gulshan Sachdeva, “TAPI: Time for the Big Push”, The Central Asia Caucasus Analyst,(2013).

[3] Wu Jiao, Zhang Yunbi, “Xi proposes a ‘new Silk Road’ with Central Asia”, China Daily, September 08, 2013.

[4] Rajat Pandit, “India expresses strong opposition to China Pakistan Economic Corridor, says challenges Indian sovereignty”, The Economic Times, July 12, 2018.

[5] Indrajit Roy, “Bringing Eurasia closer”, The Hindu, August 01, 2022.

[6] Ashok K. Behuria, Dr. M. Mahtab Alam Rizvi, “India’s Renewed Interest in Chabahar: Need to Stay the Course”, IDSA, May 13, 2015.

[7] “India and Iran sign ‘historic’ Chabahar port deal”, BBC, May 23, 2016.

[8] “Iran seeks long-term contract with India on developing Chabahar port”, The Economic Times; August 26, 2022.

[9] Manoj Kumar, Nidhi Verma, “India likely to start full operations at Iran’s Chabahar port by May end”, Reuters, March 5, 2021.

[10] Rezaul H Laskar, “India, Iran close to finalising long-term agreement on Chabahar port”, Hindustan Times, September 10, 2022.

[11] Ayjaz Wani, “India and China in Central Asia: Understanding the new rivalry in the heart of Eurasia”, ORF Occasional Paper No. 235, February 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

[12] P. Stobdan, Ashok Behuria G. Balachandran, CHABAHAR Gateway to Eurasia, (Ladakh International Centre, 2017)

[13] Maziar Motamedi, “Iran’s economy reveals power and limits of US sanctions”, Al Jazeera, February 2, 2022.

[14] US Department of State, “Readout of U.S.-India 2+2 Dialogue”, December 19, 2019.

[15] “Readout of U.S.-India 2+2 Dialogue”

[16] “India gets ‘narrow exemption’ from sanctions on Chabahar for Afghan aid”, The Telegraph, 2019.

[17] “Budget 2022: Rs 200 cr for development assistance to Afghanistan, Rs 100 cr for Chabahar port”, The Indian Express, February 02, 2022.

[18] Geeta Mohan, “Real reason why India sits out of Iran’s Chabahar-Zahedan rail link project”, India Today, July 21, 2020.

[19] Mohan, “Real reason why India sits out of Iran’s Chabahar-Zahedan rail link project”

[20] Suhasini Haidar, “Iran drops India from Chabahar rail project, cites funding delay”, The Hindu, July 14, 2020.

[21] “Zahedan-Chabahar railway to be completed by Mar. 2024”, Tehran Times, March 4, 2022.

[22] Rezaul H Laskar, “India, Iran close to finalising long-term agreement on Chabahar port”, Hindustan Times, September 10, 2022.

[23] Nicola P. Contessi, “The Great Railway Game”, Reconnecting Asia, Center for Strategics and International Studies (CSIS), March 3, 2020.

[24] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “second Trilateral Working Group Meeting between India, Iran and Uzbekistan on the joint use of Chabahar Port”, December 14, 2021.

[25] Contessi, “The Great Railway Game, Reconnecting Asia”

[26] “Explained: INSTC, the transport route that has Russia and India’s backing”, Business Standard, July 14, 2022.

[27] Nicola P. Contessi, “In the Shadow of the Belt and Road: Eurasian Corridors on the North-South Axis, Reconnecting Asia,” Center for Strategics and International Studies (CSIS), March 3, 2020.

[28] “Proposed 7,200 km long corridor INSTC to boost exports, slash transport cost by $2,500 per 15 tn of cargo: Study”, Financial Express, June 20, 2017.

[29] Hriday Ch Sarma and Dwayne R Menezes, “The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC)”, Polar Research and Policy Initiative: The Polar Connection, June 6, 2018.

[30] Contessi, “In the Shadow of the Belt and Road”

[31] “Baku set to become major Eurasian hub,” Freight Week, October 1, 2016.

[32] “ADB Approves $400 Million to Support Azerbaijan’s Rail Sector, Modernize North-South Railway Corridor”, Asian Development Bank, December 6, 2017.

[33] “Azerbaijan Railway System: Well on Track with Austrian Expertise”, Asian Development Bank, October 26, 2022.

[34] “Iran, Russia, India to meet on International North-South Corridor”, Financial Tribune, October 30, 2018.

[35] Ilham Karimli, “Iran Expands Railroad Ties with Azerbaijan”, Caspian News, January 19, 2021.

[36] Karimli, “Iran Expands Railroad Ties with Azerbaijan”

[37] Jiahang Wu ’23 History, “Railway and Iran’s International Connections and Communication”.

[38] Vali Kaleji, “Will Russia Complete Iran’s Rasht–Astara Railway?”, Eurasia Daily Monitor 19 (71) (2022).

[39] “Baku set to become major Eurasian hub,” Freight Week, October 1, 2016.

[40] Kaleji, “Will Russia Complete Iran’s Rasht–Astara Railway?”,

[41] “Tehran, Moscow eyeing $10b trade target”, Tehran Times, January 21, 2022.

[42] “Iran’s Rasht-Astara Railway To Provide The Key Link In The INSTC”, Silk Road Briefing, January 31, 2022.

[43] Keith Barrow, “Iran – Turkmenistan – Kazakhstan rail link completed”, International Railway Journal, December 03, 2014.

[44] Contessi, “In the Shadow of the Belt and Road”

[45] Stobdan, Behuria and Balachandran, CHABAHAR

[46] Vusala Abbasova, “Kazakhstan, Iran & Turkmenistan Agreed to Boost Cargo Volume via Railroad”, Caspian News; November 29, 2021.

[47] Barrow, “Iran – Turkmenistan – Kazakhstan rail link completed”

[48] “A tour through Iran as a rail freight transit country”, Rail Frieght.Com, August 17, 2022.

[49] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “Delhi Declaration of the 1st India-Central Asia Summit”, January 27, 2022.

[50] Radio Farda, “Looming Sanctions Jeopardize Expansion Of Iran’s Rail Network”, July 11, 2018.

[51] Orkhan Jalilov, “Iranian Railway Projects In Jeopardy Of Being Canned, Due To Trump’s Sanctions”, Caspian News, August 6, 2018.

[52] Radio Farda, Looming Sanctions Jeopardize Expansion of Iran’s Rail Network,

[53] World Investment report, “UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT”, United Nations Publications, New York, 2021.

[54] The World Bank, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, “Iran Economic Monitor Managing Economic Uncertainties”, 2022.

[55] “China Investments in Iran Near $27b”, Financial Tribune, January 20, 2020.

[56] Contessi, “In the Shadow of the Belt and Road”

[57] Devirupa Mitra, “Six Charts to Make Sense of India’s Budget for Foreign Policy”, The Wire, July 6, 2019.

[58] “Iran seeks long-term contract with India for development of Chabahar port”, Business Standard, August 26, 2022.

[59] “Chabahar Port Link With INSTC to Enhance Connectivity With Central Asia: Sarbananda Sonowal”, Outlook, July 31, 2022.

[60] PM India, Prime Minister’s Office, Government of India, “PM’s remarks at the SCO Summit”, September 16, 2022.

[61] “PM’s remarks at the SCO Summit”

[62] “Meeting of PM with the President of Iran on the sidelines of the SCO Summit”, PMINDIA, September 16, 2022.

[63] “Massive Container Ship Blocks Suez Canal for Second Day, Causing Long, Expensive Traffic Jam”, The Wire, March 25, 2021.

[64] “Massive Container Ship Blocks Suez Canal for Second Day”

[65] Stobdan, Behuria and Balachandran, CHABAHAR

[66] Aveek Sen, “Iran looks to Chabahar and a new transit corridor to survive US sanctions”, Atlantic Council, 2019.

Source: Observer Research Foundation